Barbara Steiner: Sunkoo, you have chosen Sacristy as the title for your exhibition. What were your reasons for this? The choice of such a term comes as something of a surprise in the non-religious context of the Bauhaus.

Kang Sunkoo: The sacristy of a church is a place where preparations for a community’s religious celebrations take place. The title embodies the themes I wanted to address in my exhibition: firstly, the occasion, the prelude to the 100th anniversary of the Bauhaus Dessau and the question of what such a ritual could mean. Secondly, the notion of sacredness at the historic Bauhaus and the almost relic-like reverence paid to the Bauhaus today. Thirdly, my personal examination of my own belief and non-belief.

I had this title in mind when I was working on the artistic design of the studio at the Schlemmer House, my first project at the Bauhaus Dessau in 2023. I then decided on the title Schrein, because it actually became a shrine, dedicated to commemorating and honouring three people who were killed by racists in Dessau.

*

BS: In your work for the studio at the Schlemmer House, you already alluded to the dark stains within this rich and outwardly radiant cultural region – such as the racially motivated murders you just mentioned. You examine the heritage of the Bauhaus critically, but I also see an affection, which is noticeably friendly.

KS: At first I felt disgusted, sensing a hypocrisy: while architectural monuments were canonized with the label of UNESCO World Heritage and became art historical pilgrimage sites, and the former Bauhaus “Masters” were idolised almost like saints, people were being murdered in Dessau because they were seen as not belonging to the place.

My sympathy lies less with the legacy itself but more with the Bauhaus Dessau of today. I followed your invitation because I have trust in your way of handling the heritage as director of the Bauhaus – both, the critical examination and the care. I like the work being done by the Building Research of the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation – it reminds me of a modern mason’s lodge, constantly taking care for its cathedral. I identify with this particular balance between the seemingly contradictory need for a certain desecration and preservation at the same time.

*

BS: You were born in South Korea and came to Germany as a child, to Düsseldorf. There you were socialised as a Catholic. What role does faith play for you today?

KS: For those who may not know that Korea has a strong Christian influence: it is probably even more of a Christian society than Germany, with a large number of active, deeply religious believers. My father comes from a Catholic family, my mother went to a Protestant church in Seoul and comes from a Buddhist family. One of my earliest memories is of a shamanistic ritual in my grandparents’ house. However previously, my parents had not brought me up with religion. I joined the Catholic Church of my own free will after arriving in Düsseldorf during my primary school years. I was an altar boy, very devout, and spent a lot of my time in churches. I left the Catholic Church many years ago – for political reasons, and because of the doubts in my faith, but I still often pray out of fear or gratitude, or when I enter sacred spaces.

*

BS: For this exhibition, the book about Josef Albers entitled “The Sacred Modernist: Josef Albers as a Catholic Artist” played an important role. Starting out from this book, you explored the religious beliefs of the Bauhäusler.

KS: During my second stay in Dessau in 2024, for the Bauhaus Residency at the Muche House, I read a wonderful catalogue text about Josef Albers from the book you mentioned. I also visited exhibitions at the Bauhaus Building and the Bauhaus Museum Dessau. I saw the collection of the Luther Memorials Foundation in Wittenberg. I learned about Albers’ Catholic childhood in the Ruhr region, where he painted wooden grave crosses with his father, a master painter. I read about his religious faith, which he practised until the end of his life, and admired his architectural sketches that analysed the proportions of cathedrals. I could imagine how Albers must have felt drawn to the first Bauhaus programme of 1919, featuring Lyonel Feininger’s woodcut Cathedral and the Bauhaus manifesto, the programme text by Walter Gropius.

I am both fascinated and disturbed by the religious and totalitarian language of this text by Gropius, phrases such as ‘the ultimate goal’ or ‘from the million hands…’. If I remember correctly, there is an issue of the magazine Frühlicht published by Bruno Taut, with the text House of Heaven, on display next to the Bauhaus manifesto in the exhibition at the Bauhaus Museum Dessau. I only recently read the secret correspondence of the Glass Chain, and it fascinates me how explicitly different ideas of faith were expressed, both in writing and in drawings, within this group, of which Walter Gropius was a member. Although Gropius apparently never contributed under his alias Mass in this ‘private chat group’, I recognise a similarly religious tone in his programme text for the Bauhaus. In all these architects, I see a connection between architecture as an artistic expression and faith. The early Bauhaus still has close connections to this.

*

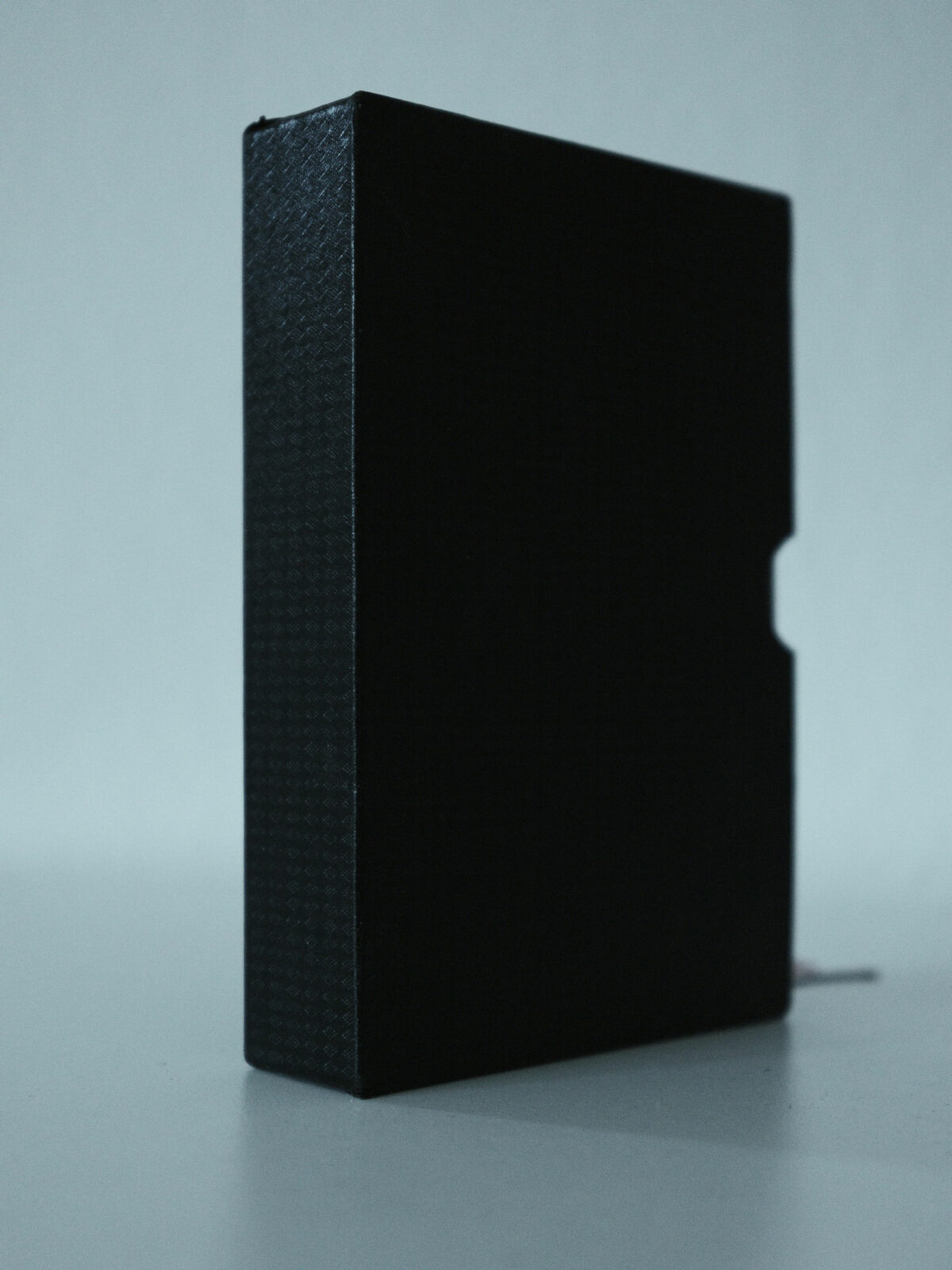

BS: An important starting point for this exhibition was the Gotteslob (Praise of God), the common prayer and hymn book of the Roman Catholic dioceses in German-speaking countries. It also became the motif for the poster. What does this book mean to you, and what role does it play in this exhibition?

KS: After many years, I rediscovered the Gotteslob in my parents’ flat. When I started working on the concept for Sacristy, I took a photograph of the book for the annual programme of the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation. That was before I had even finalised the new works for the exhibition.

*

BS: In my childhood, the Gotteslob was bound in black with gilt edging. It always had a mysterious aura for me as a child. The everyday version displayed in churches today is much lighter in colour, sometimes even with ornamentation. The Gotteslob has actually become much more secular in appearance. However, in your photo, the prayer and hymn book becomes a mystical, magical object.

KS: I wanted to photograph the book as if it were sacred architecture, or perhaps a model of such. I was thinking of the holy Kaaba, the Monolith from Kubrick’s Space Odyssey or the architecture of Mies van der Rohe. I was disappointed when I saw contemporary editions of the Gotteslob. In spite of the political difficulties I have with the Catholic Church or other institutional religions, I remain deeply connected to this mysterious aesthetic that can be found across various faiths.

This copy, from the Archdiocese of Cologne, is an elaborate edition with slipcase and gilt edging, which I received as a gift when I was baptised. On the inside of the cover, there is a beautiful, handwritten dedication from my parents, dated 3.4.1988. That was the Easter Sunday when I was baptised as Peter at the age of ten, just before I received my first communion. The position of the two ribbons indicates that the book was last used for worship on All Saints’ Day, presumably on 1 November 1988. I like the fact that this edition, with its slipcase, can stand alone like a monolith, like a memento or an accusation, although it bears the title “Praise of God”.

*

BS: Let us move on to the exhibition itself.

Please give us a summary of your thoughts on this.

KS: I make direct reference to the exhibition for the centennial, Glass | Concrete | Metal planned by the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation, which will open in the workshop wing of the Bauhaus Building after my show. In keeping with this trinitarian structure, three new works will be produced in each of these materials and paired with three objects from the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation’s building research archive.

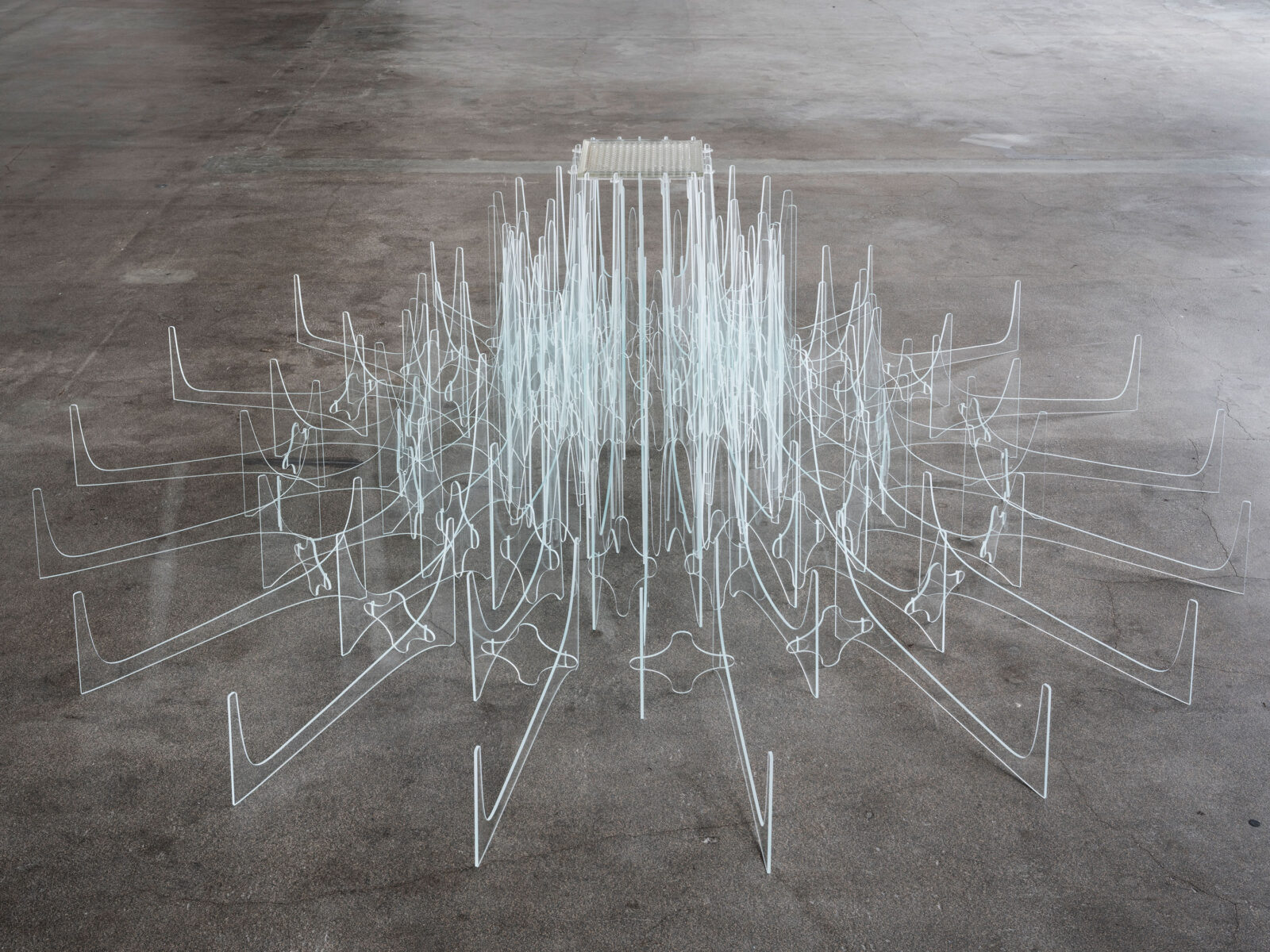

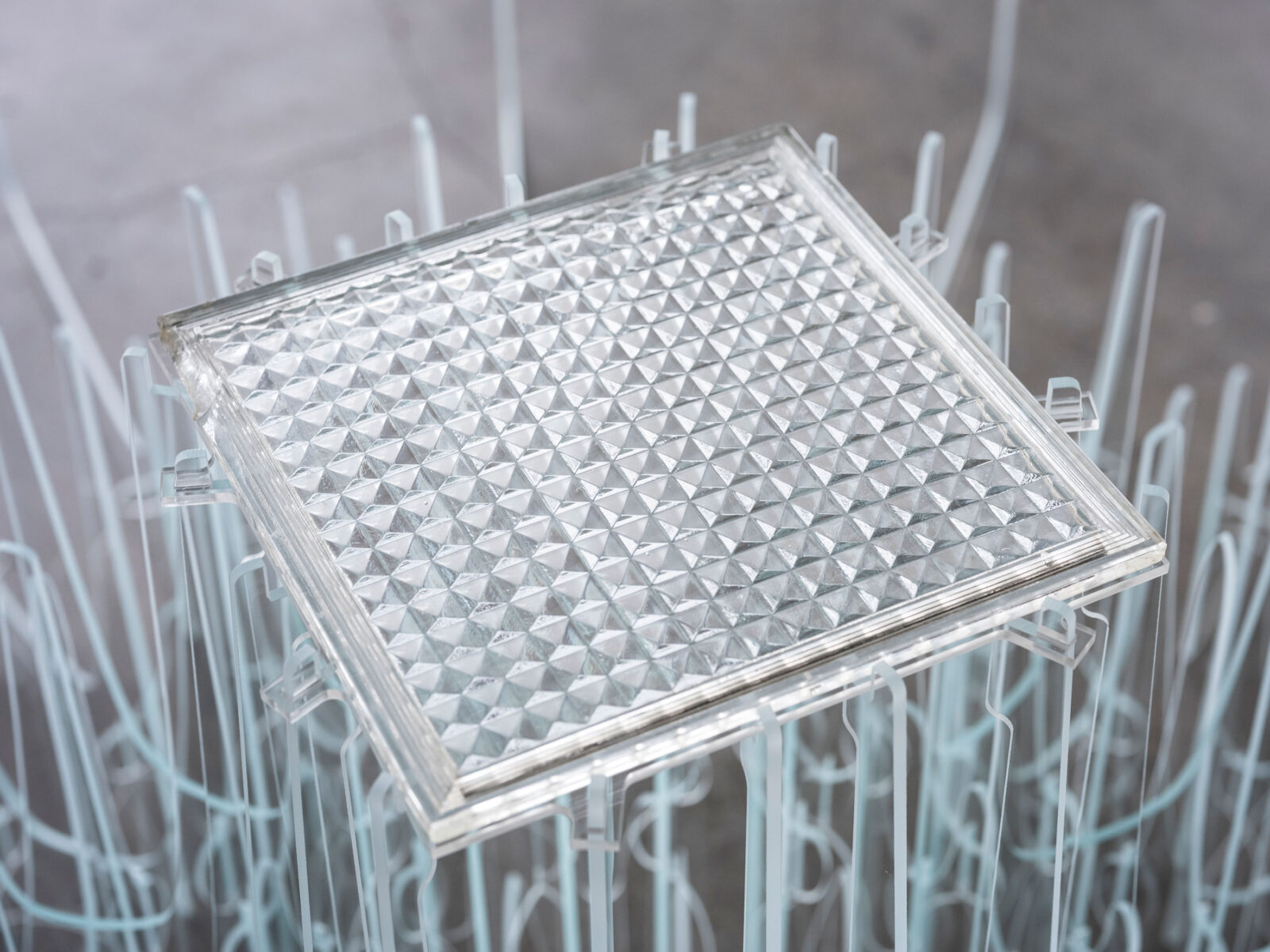

The work Monstrance is a structure made of glass panes, with a Luxfer prism glass inserted into its centre – an element previously used by Walter Gropius in the Dessau-Törten estate in 1927. The ceiling joist system Rapid is also taken from the Dessau-Törten estate.

In the work Golgotha, it is installed in the middle of a square field, surrounded by enlarged folded hands in a concrete cast.

The artwork Peter is a kinked, lying cross made of untreated stainless steel profiles. From the frontal perspective, the viewer sees a St. Peter’s Cross, an inverted cross of Jesus. This object is placed opposite the empty economical bathtubfrom the collection. The dimensions of all three of these new artworks are derived from the dimensions of Gropius’ architecture, into which they integrate. The lengths of the cross, the diameter of the monstrance and the square field of Golgotha all correspond to the five-metre axial dimension of the reinforced concrete structure that defines the space of the workshop wing.

*

BS: You only use existing lighting conditions, which accentuates the stark mood changes within the room.

KS: The room is constantly exposed to sunlight. From morning to evening, for the entire duration of the exhibition, there will be no closed curtains or artificial lighting. The objects will be positioned in such a way that the ten fields between the columns of the former weaving class are divided into two longitudinal naves, parallel to the iconic curtain walls of the workshop wing. In correlation with the economical bathtub, the artwork Peter appears like a chapel in the part of the room illuminated by diffuse daylight. The works Monstrance and Golgotha form another pairing in the other half of the room, which is illuminated by direct sunlight. They lie and stand on two pieces of parament fabric, which together form the fourth artwork, Antimension. The first and last words from the Bauhaus manifesto are embroidered into the cloths.

*

BS: Your exhibition will deliberately be shown before the opening of our centennial, leading up to the centennial. Centennials are often criticised, not least for how the veneration of the object in question can quickly become a form of relic worship.

KS: When we began working on the exhibition, you said that you, as a foundation, were working to deconstruct this cult of heightened reverence to some extent. I said that I like that we, as human beings, are always in search of such icons, believing that something can connect with us through these seemingly lifeless objects.