Anne Schneider: For many years now you have kept a personal photo archive of landscape fragments ansituations in nature. How did this start, and how do you choose your motifs?

Anna Gille: I have been collecting these landscapes and natural sites since 2011. These are places that I seek out because they interest me in terms of content, as well as motifs that I come across by chance. I am particularly interested in landscape situations in which design and overgrowth meet, and in which the human touch is sometimes more, sometimes less visible.

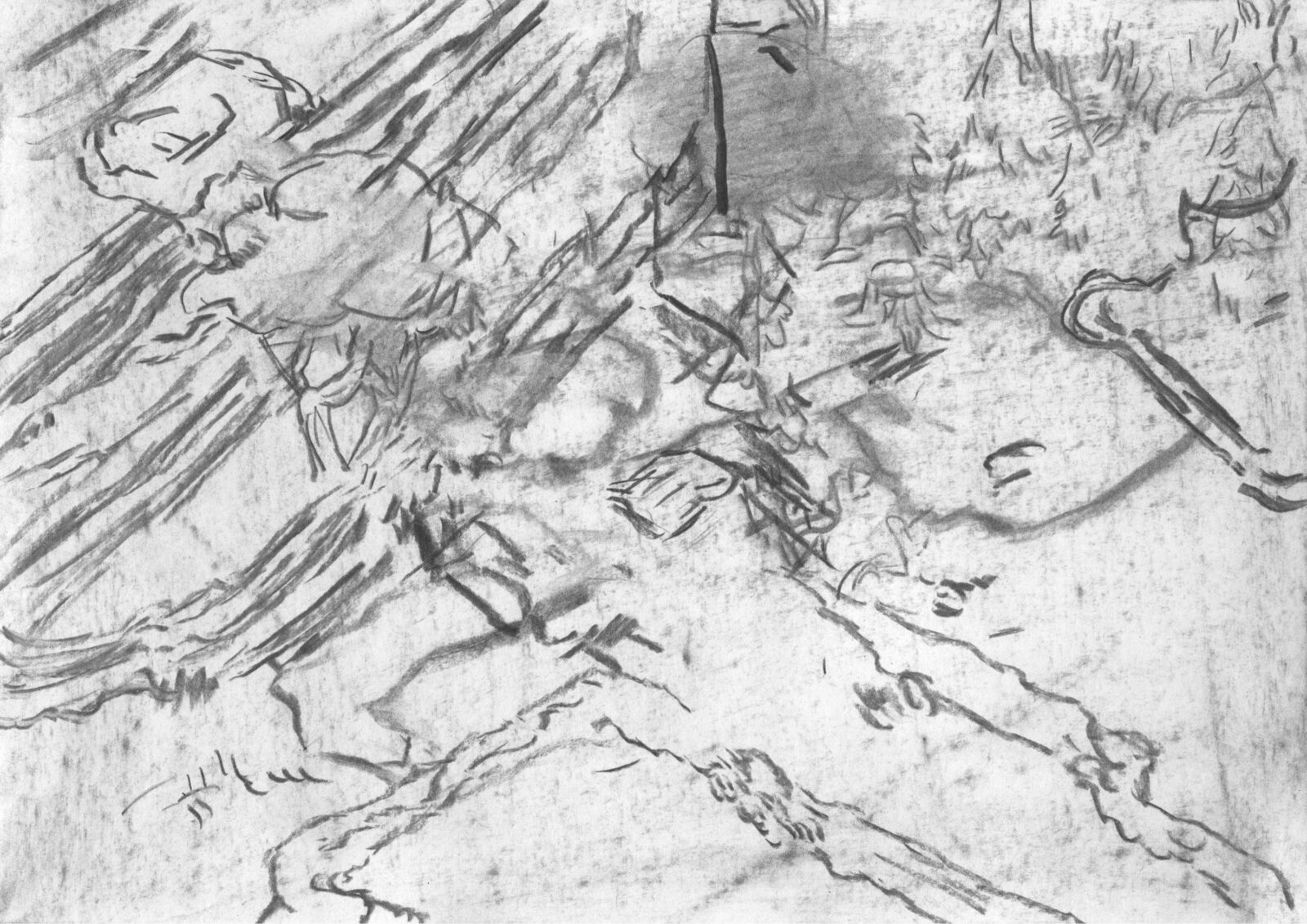

In general, my motivation for capturing a particular scenery is immediate and intuitive. I use the world that surrounds me as my material. For me, photographing the motifs primarily means collecting textures, contrasts, light and shadow, graphic elements, constellations and compositions that serve as starting points for my drawings.

*

AS: How do you continue to work with this collection for your drawings?

AG: In my drawings which are sometimes quite abstract, it’s usually not about the real, actual place itself. Instead, I use its textural properties to let something new emerge. If you like, nature supplies me with graphic inventions and ideas that I could never come up with in this abundance.

*

AS: As you said, many of your works turn out very abstract as a result, even if they are based on a real situation. Spatial references become apparent only after longer observation, and it´s not clear if these are emerging in the viewer’s own imagination or if are inherent in the picture. How far can we remove ourselves from the image of a landscape without it ceasing to be a landscape?

AG: What interests me are rather unspectacular and unspecific places and sceneries that possess great richness in form and colour. Often the motifs are laid out without horizon and are frequently in portrait format. This immediately sets up a certain distance from the classic landscape picture – which tends to be characterised by spatial depth and a visible horizon line – towards abstraction and flatness. Nevertheless, to varying degrees there’s a reference to nature in all my works.

*

Leoni Fischer: In one of our conversations you said that sometimes you feel as if you were carrying landscapes from here to there. What do you mean by that?

AG: Photographs of a specific place often end up in my archive for weeks, months or even years. To be able to really capture the structural core of a motif I usually need spatial as well temporal distance to it. As a result, the immediate experience of nature is transformed into some kind of landscape memory.

I think my view is always shaped by my personal experiences with landscapes, some of which are present only subconsciously. So, the landscape of my childhood has become an inner landscape that I’m probably constantly trying to reproduce without being aware of it.

*

LF: In preparation of the exhibition you spent four weeks in Dessau working on your pieces for the exhibition on the Raumbühne, the Spatial Stage of the Bauhaus Museum Dessau. What impressions did you gather? Are there places here that have become part of your landscape memory?

AG: Yes, definitely. Here, too, it’s mainly the non-spectacular situations that stuck in my mind. For example, the alley of birches framing the parking lot behind the Bauhaus building, which in winter has a very graphical appearance, or the planting next to a small private footpath in Gropiusallee. And then, of course, the pine trees around the Masters’ Houses!

*

LF: What do paper and charcoal mean for you in the context of your art?

AG: These are the ideal materials for me, not only because they are made from plants and relate directly to my motifs, but also because they are so essential. Charred branches and twigs, paper and cotton have been used as drawing materials and image carriers since ancient times. For me, in a way, they therefore represent drawing itself.

*

LF: The sociologist Lucius Burckhardt has thought a lot about landscape, nature and their representation; he said: it’s impossible to draw an ugly landscape.

Do you agree?

AG: When I started using landscapes from computer games as starting points for my work, I was often confronted with the question: Why are you drawing strangely pixelated landscapes from ego shooters? But for me, the question didn’t arise at all, because in the end everything is stimulation and material – whether commonly perceived as beautiful or ugly, pleasant or unpleasant. And the question could also be: Why do we see our surroundings as landscape at all? And why do we generally understand it as beautiful?