Barbara Steiner: The focus of this year‘s programme at the Bauhaus Museum Dessau revolves around the physical, social and political dimensions of the body and gestures. From several angles, we address the theme of how bodies and gestures are socially shaped and culturally embedded. However, we also speak about the power of the collective – in both an emancipatory and in a threatening sense.

In your solo exhibition, you decided to show “Les Indes Galantes” and “Morgestraich”. Why did you choose these two videos?

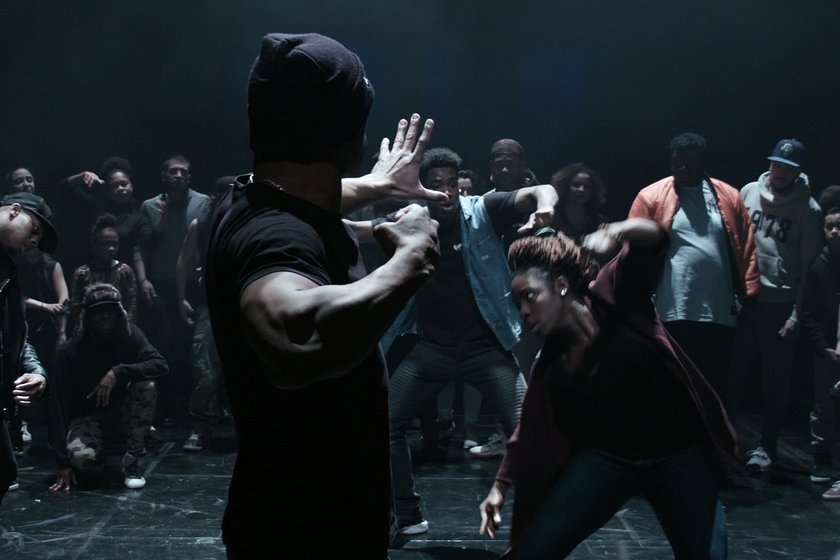

Clément Cogitore: What the videos have in common is that they both show groups of people or communities who are set in motion or placed under tension through music. “Les Indes Galantes“ is about Krump dancers. This is a dance that originated in the suburbs of Los Angeles at the end of the 1990s. My production is based on an excerpt from “Les Indes galantes”, a French baroque ballet opera from 1735, composed by Jean-Philippe Rameau and performed on the stage of the Paris Opera. “Morgestraich” is about Basel carnival cliques (Clique Seibi and Unbaggene) running on a very large treadmill in a dark theatre, to the rhythm of their drums and flutes. Of course, the treadmill is not visible in my production.

*

BS: At first, the two videos seem quite different: one of them shows a protest expressed in the form of dance, the other a carnival parade. However, both have something confrontational about them, something that directly addresses the viewer in a way that is impossible to escape.

CC: “Les Indes Galantes” is about a geopolitical and historical confrontation: it juxtaposes a protest dance invented by young dancers to express the tension and violence they experienced following the suppression of riots in the black neighbourhoods of L.A. with some of the most beautiful French music there is, even though the libretto, under the guise of enlightened humanism, is openly colonial. I think the dancers’ bodies offer a cathartic, angry response to the ideology that shaped them. In collaboration with the dancers and choreographers, we tried to question and re-examine this history and legacy through dialogues, choreography and staging.

*

BS: At first glance, “Morgestraich“ appears different. The movements of the group are rather constrained.

CC: “Morgestraich” may appear more peaceful, but only at first glance. In its own way, it testifies to age-old tensions. The Basel carnival begins with a procession through the night, accompanied by the shrill sounds of pipes and drums. Before day dawns – with an outbreak of joyousness and festivities – there is a very special moment when the lights of the city die down and the celebrations begin, in a unique way that I find mysterious, unsettling and almost sombre. This is due to the fact that this first procession is born of older and darker traditions – dances of death and medieval religious processions to ward off epidemics. The community came together and, carried by the music, crossed the darkness, invoking its fear of death to move towards healing and light.

What I find touching is this relationship between bodies and music, the history of these bodies and this music, and that is what I am trying to unfold in this exhibition. I believe that the most important aspect of “staging“ is the creation of conditions for an encounter – between bodies, faces, landscapes, places, lights, texts, music, etc. In my working process, the result of this encounter, the dialogue with participants and collaborators, in combination with cropping and montage, are what the work is all about.

*

BS: In your work I see powerful reflective aspects, in terms of both contents and media. Moving within traditions, while continuously questioning them and confronting entanglements – such as those resulting from colonial legacies – applies not only to the narrative, but also to the film itself. Are filmic means themselves to be used with caution?

CC: Filmic means must always be used with caution. The question of perspective, composition and the movement of the gaze are vital for the staging. In “Les Indes Galantes“, my intention was to create the impression of the camera being immersed within the group. It is as if the camera itself becomes one of the participants in the “battle“ unfolding before our eyes – it has a mobile, sensitive, human presence. The editing process was also very important, given the film’s blend of improvisation and choreographic composition. Sometimes I knew exactly which dancer would perform which gestures, but at other times I had no idea. Editing played a crucial role in bringing harmony and fluidity to the tension between structured choreography and improvisation, between order and chaos, so that you never really know which segments are choreographed and which are not.

*

BS: You obviously took a completely different approach in “Morgestraich“…

CC: For “Morgestraich” I wanted something much starker, more rigid. The only movement within the frame was to be that of the performer. I wanted to create a theatrical effect, an endless parade where figures continually pass by without approaching the camera. The idea was that viewers should sense that there is some kind of anomaly in this procession, without being able to identify exactly where it comes from. In contrast to “Les Indes Galantes”, which has a structured dramaturgy, music and choreography, “Morgestraich” has no dramaturgy at all. It is a repetitive, meditative march – a ritualistic walk through darkness.

*

BS: Finally, let us talk about the presentation of the works: the two films are shown in a room, on projection surfaces made of Plexiglas. What are your thoughts on this?

CC: During my initial visits to the Bauhaus, I was extremely impressed by the powerful correlation between the architecture of the buildings and the diverse forms of creativity and activities developed within them. The use of glass particularly interested me, as it created a sense of transparency and permeability throughout the spaces. I wanted to react to this transparency in my own way, by projecting the videos onto large Plexiglas screens positioned on the floor. This enables the images to merge with the location and the architecture, extending the sense of transparency and fluidity that runs through the Bauhaus Building into the darkness. It gives the images a certain materiality or physicality, and the viewers themselves are projected to the heart of the imagery and bodies, like guests on a theatre stage.